I've decided to start posting more of my published work here on gospelgal.com. Here's a recent interview I hope you enjoy.

Gospel Music: Great Stories, Flawed Characters

by Gospel Gal

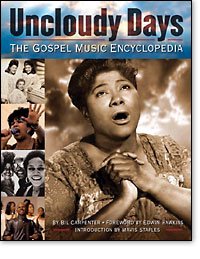

Renowned gospel music journalist and publicist Bil Carpenter is always listening to and thinking deeply about the topic. As author of Uncloudy Days: The Gospel Music Encyclopedia, Carpenter explores the stories of many of gospel's top musicians—and recounts the lives of many of the industry's lesser-known but no less significant artists. A related CD features a collection of tracks by several artists covered in the book. In this interview with Christian Music Today, Carpenter tells some of his favorite stories, shares how his frustration at work led to one of his best ideas, and weighs in on several of gospel's current significant issues.

How did you decide to write this book?

Bil Carpenter: I've always been a music fan, and it wasn't enough for me to just listen to the music. I had to know everything about the artists I liked. I'd read The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock and Roll to learn about these artists, I'd go to the drugstore, I'd get a magazine.

In my late teens, when I started to get into gospel music, there were no magazines with gospel artists in them. So I just started collecting information, and when I started writing for The Washington Post, I was always trying to pitch articles on gospel artists, so I could interview them and learn about them.

After a few years, I'd become friends with artists like Marion Williams, who was with the Clara Ward singers. I was just like a kid at Christmas. These older artists told me these great stories about being on the road with Sam Cooke and Mahalia Jackson, and it was like a grandfather telling the grandkid about the good old days. I would just sop it up.

Then they started dying. Marion died, and some others died, and I felt these stories have to be told. But I wasn't thinking about how to tell them.

What made you think these important stories should be compiled as an encyclopedia?

Carpenter: One day, I was feeling sort of frustrated as a publicist. One of my clients had made me angry (chuckling). When I get really angry, I clean up. So, I was cleaning up my closet and discovered some profiles I'd written for a book I'd planned to do on black entertainers. I thought, This is what I can do. I can do a gospel encyclopedia.

At first, I figured it would take me about four weeks to write 100 profiles. But as I interviewed people, they told me stories about the people who influenced them—people I'd never heard of. So, my whole month theory turned into over a year. The 100 artists became more than 600.

What are some of the interesting stories you discovered?

Carpenter: I've written about Willa Dorsey, who was one of the first black women to integrate white churches in the '50s and '60s as a singer. She spoke about how that felt and how she was treated. She was a trailblazer, and she's almost been forgotten. I also write about Sara Jordan Powell, who claims that Ray Charles stole her version of "America the Beautiful."

You tell of the story of Sister Rosetta Tharpe, who was torn between her desire to do mainstream music and her desire to be part of the gospel community. It seems like that is one of the stories for the ages, emblematic of the tensions many artists face.

Carpenter: Yeah. I think it will always be, because it goes back to the Scripture that says to be in the world but not of the world. How long can you be around something and not be a part of it? Rosetta Tharpe became a star doing gospel music that crossed over, but because it crossed over, offers came to do secular music, which she did. At the same time, in her heart she was still a gospel singer, and she still felt a need to minister. But the church of the time felt that you couldn't be at the club on Saturday night and come to church on Sunday morning. So once she was doing secular music, she had to stay out there, because no one would accept her back.

Because we don't live in a vacuum, or in a religiously homogenous society, those issues still exist. For example, when Yolanda Adams sang the song "Imagine" at a John Lennon tribute, some church folks felt she shouldn't have been on the show. Others didn't mind her doing the show, but felt she should have sung gospel. Still others were all for it, were happy to see her there. So you have all these different thought processes, and I don't know who's right and who's wrong. It's real tricky, and I don't think it's getting any easier, because most of the younger gospel artists want to sing gospel, but they want to be in the secular spotlight.

Because we don't live in a vacuum, or in a religiously homogenous society, those issues still exist. For example, when Yolanda Adams sang the song "Imagine" at a John Lennon tribute, some church folks felt she shouldn't have been on the show. Others didn't mind her doing the show, but felt she should have sung gospel. Still others were all for it, were happy to see her there. So you have all these different thought processes, and I don't know who's right and who's wrong. It's real tricky, and I don't think it's getting any easier, because most of the younger gospel artists want to sing gospel, but they want to be in the secular spotlight.You also talk about several artists who find themselves on music's color line, between CCM and black gospel music.

Carpenter: That's true. And I've also noticed that while we often hear about problems that black artists have in the white Christian world, we rarely hear how racist the black Christian world is. I'm friends with Martha Munizzi [who is white] and her husband, Dan. When she won the Stellar Award for best new artist in 2005, a lot of people were very upset. People said, "Who is she, where did she come from, and why is she winning our award?" I noticed the same thing when I did PR for Vicki Yohe and her album Because of Who You Are. We went to a TV station to record a black TV show, for her to sing the song. They did not know she was white. Everybody was friendly with me, but sort of cold toward her. She told me that happens a lot. They thought she was going to sing some sort of CCM music. But after she sang, the same people who acted like they didn't want her to touch them when she walked by, they rushed to her and said, "I had no idea that was you [on the radio]—you're so wonderful!"

It's common to hear that white Christian radio will not accept black artists. Yet we have a Larnelle Harris, we had a BeBe and CeCe Winans, we have a Nicole C. Mullen—all on "white radio." Now we have Vicki Yohe and Martha Munizzi. But I've had radio announcers tell me that they wouldn't play them, also.

The book includes more than one story of people who had to hold on to their faith when they were mistreated by people in the gospel music industry.

Carpenter: One of those very compelling stories is that of Rev. Willie Morganfield. He wrote this gospel classic, "What Is This," that Brother Joe May claimed to have written. Because of Brother Joe May's actions, and because the song was such a well-written, classic-sounding song, people thought it was a hymn. So all kinds of artists started recording it as a public domain song. It took years for Rev. Morganfield to get his copyright back. He died unexpectedly, just three weeks after I interviewed him.

Another compelling story is that of Phillip Bailey [from Earth Wind & Fire]. After becoming a Christian and recording a gospel project, he ended up leaving the gospel music industry disillusioned. He was pressured to create gospel music that sounded like his secular pop, and he was also surprised at the racism, lack of integrity and profiteering he saw. Still, that didn't change his faith. He realized that faith isn't about those people, but about his personal relationship with God.

There seems to be a thread of truth-telling throughout the book. For example, you don't avoid talking about the personal or financial struggles of some artists in the book. How have people responded to that?

Carpenter: Well, I've gotten the most flack from people who were close to James Cleveland. [The book describes the scandal and financial disarray that emerged after Cleveland's death, including an allegation of sexual misconduct involving a teenage boy]. I was in Los Angeles at the House of Blues, and the Clara Ward singers were there. One of the members took me outside behind the building and argued with me about the James Cleveland entry. She didn't say that any of the information was false—she just didn't like that I'd written about his wealth or the scandals. But I'd tried to speak to people who were close to him, and they refused to talk to me. Another author circulated a petition to have the book removed from stores in Chicago because he was disgusted by that entry.

Why did you feel it was important to tell those stories that point out the personal failures of gospel artists—or the failures of the industry?

Carpenter: I think that many people are turned off by the hypocrisy they see in the church. As long as we put our psalmists, musicians, and pastors on a pedestal and we cover it when they mess up, we create an unrealistic situation for people to aspire to. But when you let people know that even great people struggle, but they overcome and triumph, it gives them hope. We're striving toward perfection, toward the more Christlike life. And that takes time, and you get off the road sometimes, and hopefully you get back on the road. That's why I felt it was important for people to know.

Still, the book doesn't have a scandalous tone. And there are plenty of stories of triumph, even in difficult circumstances.

Carpenter: Right. Most of the stories are stories of triumph. One is Kirk Franklin's story of overcoming his addiction to pornography. Another is the story of Willa Ward, the sister of Clara Ward. Their mother, Gertrude, was a stage mother in the worst sense of the word. She kicked Willa out of the group, because she felt that Clara was the star. But Willa has forgiven her mother, and now allows Madelyn Thompson, one of the Clara Ward Singers, to preserve the family heritage. The way she put her feelings aside to forgive is a triumph.

Then there are stories like Douglas Miller's. One of the darkest days of his life was also the day when he wrote the famous song, "My Soul Has Been Anchored in the Lord." There were guys standing outside of his hotel room with guns, ready to kill him, because of a dispute with his record label.

With his Christian record label?

Carpenter: Yes. Out of that terrible period was born this song that has touched people's lives. People have shared with him that the song has kept them from committing suicide.

The overarching story is how, in spite of the ups and downs these artists experienced, they maintained their faith, or it was strengthened by what they went through. That's where the title comes from. "Uncloudy Days" is a song talking about getting through this world of many storms, to that place where there are no more clouds.

1 comment:

I have read and enjoyed UNCLOUDY DAYS - gave me greater insight into the struggles and triumphs of those who came before us...thank you!

Post a Comment