"I have nothing against contemporary gospel musicians, with their suave choral arrangements and eclecticism. They are the inheritors. But there is no thrill like listening to those who invented the language."

--Margo Jefferson, in "Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing: Soaring Hallelujahs of the Original Gospel Music," The New York Times, August 25, 2005

Saturday, February 25, 2006

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

What's Jon Gibson Up To?

Have you ever just lost track of a favorite artist? A friend of mine introduced me to the work of Jon Gibson a few years ago, but I haven't heard much from him lately. Turns out, he's on MySpace. Here's a link to his page, where you can view footage of a recent performance. You can also listen to my favorite Jon Gibson song, "Fly With the Wind." During a really crummy, difficult period in my life, I recorded that song over and over on both sides of a cassette I'd listen to whenever I got in the car. I still listen to that song whenever I need to believe that I can triumph over tough times.

Have you ever just lost track of a favorite artist? A friend of mine introduced me to the work of Jon Gibson a few years ago, but I haven't heard much from him lately. Turns out, he's on MySpace. Here's a link to his page, where you can view footage of a recent performance. You can also listen to my favorite Jon Gibson song, "Fly With the Wind." During a really crummy, difficult period in my life, I recorded that song over and over on both sides of a cassette I'd listen to whenever I got in the car. I still listen to that song whenever I need to believe that I can triumph over tough times.Anyway, it's good to know that he's around, and doing well. Now, if I could just find out what Chris Willis is up to . . .

Update: Well, OK. Mystery solved.

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

Update: Boys Choir of Harlem

An update related to this post:

Harlem Boys Choir Faces Eviction (CNN.com): "There have been many moments of greatness over the decades for the Boys Choir of Harlem -- concerts around the world, audiences including Nelson Mandela and Pope John Paul II. But the choir has also struggled in recent years with financial troubles, and management issues in the wake of a sexual abuse scandal."

Boys Choir of Harlem Loses Legal Round (1010 WINS): "A Manhattan judge refused to issue a temporary restraining order Friday that would have let the famed Boys Choir of Harlem stay in its rehearsal space but she scheduled a hearing on whether the eviction was legal."

Boys Choir of Harlem Prevented From Entering Their Building (Wavy.com): "Education officials say the choir's financial and management problems after a sex scandal prompted the eviction."

Choir's Founder Barred From Building (CNN.com): "'The choir is not disbanded,' [founder Walter]Turnbull said. 'We will continue to rehearse, and we will continue to honor our contractual obligations because we're paid for every performance.'"

New Choir Big Sings Sad Tune (huh?) (NY Daily News): "Mary Eustace Valmont, the embattled choir's acting executive director, said City Hall's decision to evict choir officials from a Harlem public school on Feb. 1 has caused the group to cancel all performances, including a trip to Cuba because its singers cannot rehearse."

Here's a roundup of additional stories, courtesy of Topix.net.

Harlem Boys Choir Faces Eviction (CNN.com): "There have been many moments of greatness over the decades for the Boys Choir of Harlem -- concerts around the world, audiences including Nelson Mandela and Pope John Paul II. But the choir has also struggled in recent years with financial troubles, and management issues in the wake of a sexual abuse scandal."

Boys Choir of Harlem Loses Legal Round (1010 WINS): "A Manhattan judge refused to issue a temporary restraining order Friday that would have let the famed Boys Choir of Harlem stay in its rehearsal space but she scheduled a hearing on whether the eviction was legal."

Boys Choir of Harlem Prevented From Entering Their Building (Wavy.com): "Education officials say the choir's financial and management problems after a sex scandal prompted the eviction."

Choir's Founder Barred From Building (CNN.com): "'The choir is not disbanded,' [founder Walter]Turnbull said. 'We will continue to rehearse, and we will continue to honor our contractual obligations because we're paid for every performance.'"

New Choir Big Sings Sad Tune (huh?) (NY Daily News): "Mary Eustace Valmont, the embattled choir's acting executive director, said City Hall's decision to evict choir officials from a Harlem public school on Feb. 1 has caused the group to cancel all performances, including a trip to Cuba because its singers cannot rehearse."

Here's a roundup of additional stories, courtesy of Topix.net.

Karen Clark Sheard: Back From the Dead

Interview by LaTonya Taylor

For gospel's Karen Clark Sheard, music ministry has always been a fact of life. As one of the Clark Sisters, she and sisters Dorinda, Twinkie and Jacky revolutionized the genre in ways that still reverberate throughout the industry. But Karen didn't stop there. She began a solo career in 1997 with Finally Karen, taking her distinctive vocal acrobatics to a new audience. Since then, she's weathered a life-threatening illness, produced three more well-received albums, and balanced her roles as a first lady and mother of two talented teens with a busy career and growing speaking ministry. In this interview, she talks about her new album, It's Not Over, her growth as a writer, her interaction with mainstream artists, and why she's recorded a favorite song—again.

On this new album, you chose to reprise "It's Not Over" from 2002's Second Chance—-and even made it the title cut. What was the reason for that?

Karen Clark Sheard: Before I recorded Second Chance, I had been very sick following unexpected complications from hernia surgery. I developed a blood clot in my lungs, then another in my leg. Other problems developed, and I was in a coma for three and a half weeks. The doctors gave me a two percent chance of survival. Then, I was bedridden for so long that my doctor told me I'd have to go to rehab to learn how to use my limbs again. When I heard that, I thought, I won't be able to sing anymore. I won't be able to play piano. The Enemy really tried to attack my mind, slapping me with that thought over and over: Wow, it might be over for me.

But God awesomely proved himself. He gave me strength. And one day, he spoke to me: "Go to the piano." I went over to the piano I thought I wasn't ever going to be able to play, and I began to play, and that's when this song came about: "It's not over / until God says it's over." I recorded that song on Second Chance, after I recovered, and it's become a weapon for me. Singing that song is like slapping the Devil's face. It's saying, "You thought it was over for me, you tried to make me think that it was over, but I'm going to title this album 'It's Not Over.'"

So, to keep slapping, you keep recording it.

Sheard: (laughs) Right.

One of the things that seems significant about this album is that it's your first with Word—-but not really, because The Clark Sisters recorded with Word.

Sheard: Yes! It's like I'm coming back home. When Elektra disbanded its gospel division, Word reached out to me, and I decided to come back and see how they can take me to the next dimension. I felt that Word could take me more deeply into the Christian market. They're doing a great job so far.

What do you think that next dimension will look like for you?

Sheard: With this CD, I started doing something out of my comfort zone, that I believe that God allowed—writing and producing. I would never have thought I could do that—I just thought I was so incompetent . . .

Wait. This is Karen Clark Sheard, talking about feeling incompetent?

Sheard: I'm telling you, years ago, I tried it, and I said, "No, I am not gonna embarrass myself and start writing." But with this particular project, people prophesied to me and said, "You're gonna start writing." And I was looking at them like, I think you're off, prophet. But all of a sudden, God just started blessing me to write. On this album, my son J. Drew and I co-wrote "A Living Testimony," which he produced. I also wrote "Authority" with Israel Houghton and Aaron Lindsey. So, I think that's part of the dimension that God is taking me to.

You've spoken before about your childhood, saying it was very strong in terms of musical training, but that you also had to sacrifice some typical childhood experiences.

Sheard: Yes. I find all of my sisters saying the same thing. Of course, my late mother [Dr. Mattie Moss Clark] was a great legend in the Church of God in Christ, and she decided that she wanted to bring her girls up in the church, and support us in the gift that God had given us. So we'd be out playing, and we'd hear her calling our names all the way down the street. I know they thought my mother was a crazy woman (laughing): "Come on y'all, it's rehearsal time." So we kind of missed out on some play time. Then a lot of times she would wake us up early in the morning, you know, and say "God gave me a song." At 3 or 4 o'clock in the morning! And we were like, "God gave you a song at 4 o'clock in the morning? Are you serious?" It's really funny now, but back then it was hard sometimes.

Now, it's paying off, because you just never know what God's plan is. And sometimes, I find myself encouraging my daughter [Kierra Sheard] the same way. Sometimes she's not free to hang out with friends. Sometimes she would rather stay home when she's been called for an engagement, and I can sympathize, because I know what that's like. But I can instill in her a strong foundation, the way my mother did with the Clark Sisters.

Both of your children are musically gifted. What has it been like to cultivate their development as artists?

Sheard: My son [J. Drew] is 16, and my daughter is 18. It takes me back to the way my mother brought me up. What helps is that my children have a love for music and ministry in them—it's not something I have to push them toward or make them do. Because they're still so young, it's been a little difficult at times, but it's all been good. God's given them strength and blessing, and opened doors that have, overall, outweighed some of the bad days and sacrifices. Of course, my husband has just been the engine, the support that's driving us. He's my business manager. I can't do without my man (laughs). I have to say that.

He sounds very supportive.

Sheard: He's been a great leader—-of course, he's my pastor, too. I'm up constantly, giving of myself in ministry, and through listening to him as a leader, and being fed the Word of God, my job becomes easy for me.

Your cousin, J Moss, has done a lot of production on your solo albums. Have you ever had to work out a creative difference?

Sheard: Oooh, yes (laughing). Many. Maannny!

By the time we hear your songs, it sounds like everything's gone smoothly.

Sheard: Oh, no. Once, when we were in the studio working on a track for Second Chance, I told J, "J, I don't want to sing that hard on this part—I want to sing light." But he kept telling me, "You need to do it like this, you need to do it like that." Finally I just said, "You come in here and do it, then, yourself" (laughing)! "You want it done so bad, you do it!" So we just fought—-that record was really difficult for us. But it drew us closer because we learned how the other works. J is more like my brother than my cousin, and we enhance each others' ministries. I respect him as my producer, and he respects me as an artist. So we learned how to deal with each other, and now we know what to expect, and it's easier to work together.

A lot of mainstream artists mention you as an influence. And you've had the opportunity to collaborate, to sing onstage or to minister. Would you share about that?

Sheard: It's really an honor to be recognized by such mega-artists. I was asked to sing one of Mariah Carey's inspirational songs on a tribute album for her, and I thought that was so awesome. I felt like it was so major just to have been asked. I was told that when she heard that I'd be part of the project, she was jumpin' up like I was a mega-star!

When I finally got a chance to talk with her, she began to cry and told me that she'd admired me from afar. That was really encouraging, because I've been criticized for locking arms with secular artists. But I know that I'm ministering to those artists as well as having a good time together. When I hear that someone was blessed by my music, or helped out of a difficult situation, that lets me know that I'm doing what God called me to do. So if I have to be talked about and criticized, so be it, as long as God gets the glory.

How do you handle that sort of criticism? It can't feel good.

Sheard: I'd understand the criticism if I were crossing the line and compromising, but I'm not doing that. These artists call me for ministry, and I do exactly that. The criticism hurts, but it helps me to know that God is pleased with what I'm doing. Fortunately, my church prays for me and encourages me. I'm not going over there to cross over, and I believe when someone reaches out to you, you're supposed to show yourself friendly, not shun them. You don't know whose life you may touch. And mainstream artists have shared with me that they see a difference: Your music blessed me. You didn't come over here and do what we do. But you have let your light shine.

I'm not going to lie: I've received offers to sing secular music. One company even offered me a deal, as long as I didn't sing inspirational music. But I've taken a stand. I held up my banner for God. And that's because of what my mother instilled in me. She taught me that you have to have a strong foundation. A lot of our gospel artists waver because they lack that foundation. You have to know that there are certain things you cannot do representing gospel, and God. I think that's why I'm where I am today, because God can trust me, even when I go into a secular arena. He can trust me to continue to live a Christian lifestyle.

I'm sure some of those opportunities would have allowed you to make a very good living.

Sheard: Those offers have been tempting, because of the setbacks we have had in our own gospel world. Gospel was not accepted, when I was growing up as one of the Clark Sisters, as it is now. But I'm blessed today, wanting for nothing. And I can say I didn't have to go to the world to get this. God has blessed me and opened many doors.

Saturday, February 18, 2006

Gospel Geek Alert: Album Cover Roundup

Now, this is cool. A website called albumart.org tracks CD and DVD covers. This promises to be helpful on a few levels. For example, not only can you trace an artist's various hairstyles through the years (valuable, I know), but it's also a good way to fill in any gaps you have in your knowledge of an artist's discography. I've just done a bit of browsing so far, but it seems to have an impressive archive. (Hat tip: www.lifehacker.com, illustration credit: albumart.org)

Now, this is cool. A website called albumart.org tracks CD and DVD covers. This promises to be helpful on a few levels. For example, not only can you trace an artist's various hairstyles through the years (valuable, I know), but it's also a good way to fill in any gaps you have in your knowledge of an artist's discography. I've just done a bit of browsing so far, but it seems to have an impressive archive. (Hat tip: www.lifehacker.com, illustration credit: albumart.org)In other album art news, I learned about the work of Harvey, an artist who illustrated many 1960s-era gospel album covers, through Bob Marovich's website, www.gospelmemories.com. The gallery on the

site is worth browsing. Apparently Harvey's identity is a mystery.

ThinkChristian.net recently highlighted

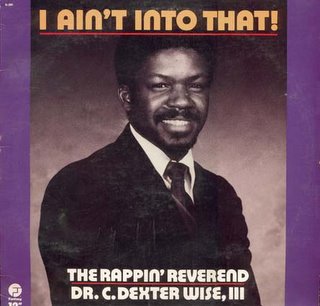

Purgatorio's Divine Vinyl collection of Christian album art from the 1970s. Whooooooo. It's the visual equivalent of The Annoying Music Show (as well

Purgatorio's Divine Vinyl collection of Christian album art from the 1970s. Whooooooo. It's the visual equivalent of The Annoying Music Show (as well as the source of the Rappin' Reverend cover at right). *Shaking head* My [Christian] people, my [Christian] people.

So, What Do You Talk About Here?

Here's a Word Cloud (get yours, and have it put on a t-shirt, at www.snapshirts.com) including words from recent posts:

So, which of these topics has been most interesting to you so far? What gospel-music issues or news stories are you most interested in conversing about?

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

Gospel Music: Great Stories, Flawed Characters

Friends,

I've decided to start posting more of my published work here on gospelgal.com. Here's a recent interview I hope you enjoy.

Gospel Music: Great Stories, Flawed Characters

by Gospel Gal

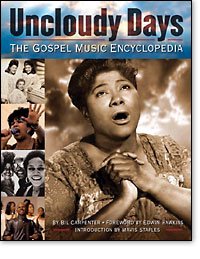

Renowned gospel music journalist and publicist Bil Carpenter is always listening to and thinking deeply about the topic. As author of Uncloudy Days: The Gospel Music Encyclopedia, Carpenter explores the stories of many of gospel's top musicians—and recounts the lives of many of the industry's lesser-known but no less significant artists. A related CD features a collection of tracks by several artists covered in the book. In this interview with Christian Music Today, Carpenter tells some of his favorite stories, shares how his frustration at work led to one of his best ideas, and weighs in on several of gospel's current significant issues.

How did you decide to write this book?

Bil Carpenter: I've always been a music fan, and it wasn't enough for me to just listen to the music. I had to know everything about the artists I liked. I'd read The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock and Roll to learn about these artists, I'd go to the drugstore, I'd get a magazine.

In my late teens, when I started to get into gospel music, there were no magazines with gospel artists in them. So I just started collecting information, and when I started writing for The Washington Post, I was always trying to pitch articles on gospel artists, so I could interview them and learn about them.

After a few years, I'd become friends with artists like Marion Williams, who was with the Clara Ward singers. I was just like a kid at Christmas. These older artists told me these great stories about being on the road with Sam Cooke and Mahalia Jackson, and it was like a grandfather telling the grandkid about the good old days. I would just sop it up.

Then they started dying. Marion died, and some others died, and I felt these stories have to be told. But I wasn't thinking about how to tell them.

What made you think these important stories should be compiled as an encyclopedia?

Carpenter: One day, I was feeling sort of frustrated as a publicist. One of my clients had made me angry (chuckling). When I get really angry, I clean up. So, I was cleaning up my closet and discovered some profiles I'd written for a book I'd planned to do on black entertainers. I thought, This is what I can do. I can do a gospel encyclopedia.

At first, I figured it would take me about four weeks to write 100 profiles. But as I interviewed people, they told me stories about the people who influenced them—people I'd never heard of. So, my whole month theory turned into over a year. The 100 artists became more than 600.

What are some of the interesting stories you discovered?

Carpenter: I've written about Willa Dorsey, who was one of the first black women to integrate white churches in the '50s and '60s as a singer. She spoke about how that felt and how she was treated. She was a trailblazer, and she's almost been forgotten. I also write about Sara Jordan Powell, who claims that Ray Charles stole her version of "America the Beautiful."

You tell of the story of Sister Rosetta Tharpe, who was torn between her desire to do mainstream music and her desire to be part of the gospel community. It seems like that is one of the stories for the ages, emblematic of the tensions many artists face.

Carpenter: Yeah. I think it will always be, because it goes back to the Scripture that says to be in the world but not of the world. How long can you be around something and not be a part of it? Rosetta Tharpe became a star doing gospel music that crossed over, but because it crossed over, offers came to do secular music, which she did. At the same time, in her heart she was still a gospel singer, and she still felt a need to minister. But the church of the time felt that you couldn't be at the club on Saturday night and come to church on Sunday morning. So once she was doing secular music, she had to stay out there, because no one would accept her back.

Because we don't live in a vacuum, or in a religiously homogenous society, those issues still exist. For example, when Yolanda Adams sang the song "Imagine" at a John Lennon tribute, some church folks felt she shouldn't have been on the show. Others didn't mind her doing the show, but felt she should have sung gospel. Still others were all for it, were happy to see her there. So you have all these different thought processes, and I don't know who's right and who's wrong. It's real tricky, and I don't think it's getting any easier, because most of the younger gospel artists want to sing gospel, but they want to be in the secular spotlight.

Because we don't live in a vacuum, or in a religiously homogenous society, those issues still exist. For example, when Yolanda Adams sang the song "Imagine" at a John Lennon tribute, some church folks felt she shouldn't have been on the show. Others didn't mind her doing the show, but felt she should have sung gospel. Still others were all for it, were happy to see her there. So you have all these different thought processes, and I don't know who's right and who's wrong. It's real tricky, and I don't think it's getting any easier, because most of the younger gospel artists want to sing gospel, but they want to be in the secular spotlight.

You also talk about several artists who find themselves on music's color line, between CCM and black gospel music.

Carpenter: That's true. And I've also noticed that while we often hear about problems that black artists have in the white Christian world, we rarely hear how racist the black Christian world is. I'm friends with Martha Munizzi [who is white] and her husband, Dan. When she won the Stellar Award for best new artist in 2005, a lot of people were very upset. People said, "Who is she, where did she come from, and why is she winning our award?" I noticed the same thing when I did PR for Vicki Yohe and her album Because of Who You Are. We went to a TV station to record a black TV show, for her to sing the song. They did not know she was white. Everybody was friendly with me, but sort of cold toward her. She told me that happens a lot. They thought she was going to sing some sort of CCM music. But after she sang, the same people who acted like they didn't want her to touch them when she walked by, they rushed to her and said, "I had no idea that was you [on the radio]—you're so wonderful!"

It's common to hear that white Christian radio will not accept black artists. Yet we have a Larnelle Harris, we had a BeBe and CeCe Winans, we have a Nicole C. Mullen—all on "white radio." Now we have Vicki Yohe and Martha Munizzi. But I've had radio announcers tell me that they wouldn't play them, also.

The book includes more than one story of people who had to hold on to their faith when they were mistreated by people in the gospel music industry.

Carpenter: One of those very compelling stories is that of Rev. Willie Morganfield. He wrote this gospel classic, "What Is This," that Brother Joe May claimed to have written. Because of Brother Joe May's actions, and because the song was such a well-written, classic-sounding song, people thought it was a hymn. So all kinds of artists started recording it as a public domain song. It took years for Rev. Morganfield to get his copyright back. He died unexpectedly, just three weeks after I interviewed him.

Another compelling story is that of Phillip Bailey [from Earth Wind & Fire]. After becoming a Christian and recording a gospel project, he ended up leaving the gospel music industry disillusioned. He was pressured to create gospel music that sounded like his secular pop, and he was also surprised at the racism, lack of integrity and profiteering he saw. Still, that didn't change his faith. He realized that faith isn't about those people, but about his personal relationship with God.

There seems to be a thread of truth-telling throughout the book. For example, you don't avoid talking about the personal or financial struggles of some artists in the book. How have people responded to that?

Carpenter: Well, I've gotten the most flack from people who were close to James Cleveland. [The book describes the scandal and financial disarray that emerged after Cleveland's death, including an allegation of sexual misconduct involving a teenage boy]. I was in Los Angeles at the House of Blues, and the Clara Ward singers were there. One of the members took me outside behind the building and argued with me about the James Cleveland entry. She didn't say that any of the information was false—she just didn't like that I'd written about his wealth or the scandals. But I'd tried to speak to people who were close to him, and they refused to talk to me. Another author circulated a petition to have the book removed from stores in Chicago because he was disgusted by that entry.

Why did you feel it was important to tell those stories that point out the personal failures of gospel artists—or the failures of the industry?

Carpenter: I think that many people are turned off by the hypocrisy they see in the church. As long as we put our psalmists, musicians, and pastors on a pedestal and we cover it when they mess up, we create an unrealistic situation for people to aspire to. But when you let people know that even great people struggle, but they overcome and triumph, it gives them hope. We're striving toward perfection, toward the more Christlike life. And that takes time, and you get off the road sometimes, and hopefully you get back on the road. That's why I felt it was important for people to know.

Still, the book doesn't have a scandalous tone. And there are plenty of stories of triumph, even in difficult circumstances.

Carpenter: Right. Most of the stories are stories of triumph. One is Kirk Franklin's story of overcoming his addiction to pornography. Another is the story of Willa Ward, the sister of Clara Ward. Their mother, Gertrude, was a stage mother in the worst sense of the word. She kicked Willa out of the group, because she felt that Clara was the star. But Willa has forgiven her mother, and now allows Madelyn Thompson, one of the Clara Ward Singers, to preserve the family heritage. The way she put her feelings aside to forgive is a triumph.

Then there are stories like Douglas Miller's. One of the darkest days of his life was also the day when he wrote the famous song, "My Soul Has Been Anchored in the Lord." There were guys standing outside of his hotel room with guns, ready to kill him, because of a dispute with his record label.

With his Christian record label?

Carpenter: Yes. Out of that terrible period was born this song that has touched people's lives. People have shared with him that the song has kept them from committing suicide.

The overarching story is how, in spite of the ups and downs these artists experienced, they maintained their faith, or it was strengthened by what they went through. That's where the title comes from. "Uncloudy Days" is a song talking about getting through this world of many storms, to that place where there are no more clouds.

I've decided to start posting more of my published work here on gospelgal.com. Here's a recent interview I hope you enjoy.

Gospel Music: Great Stories, Flawed Characters

by Gospel Gal

Renowned gospel music journalist and publicist Bil Carpenter is always listening to and thinking deeply about the topic. As author of Uncloudy Days: The Gospel Music Encyclopedia, Carpenter explores the stories of many of gospel's top musicians—and recounts the lives of many of the industry's lesser-known but no less significant artists. A related CD features a collection of tracks by several artists covered in the book. In this interview with Christian Music Today, Carpenter tells some of his favorite stories, shares how his frustration at work led to one of his best ideas, and weighs in on several of gospel's current significant issues.

How did you decide to write this book?

Bil Carpenter: I've always been a music fan, and it wasn't enough for me to just listen to the music. I had to know everything about the artists I liked. I'd read The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock and Roll to learn about these artists, I'd go to the drugstore, I'd get a magazine.

In my late teens, when I started to get into gospel music, there were no magazines with gospel artists in them. So I just started collecting information, and when I started writing for The Washington Post, I was always trying to pitch articles on gospel artists, so I could interview them and learn about them.

After a few years, I'd become friends with artists like Marion Williams, who was with the Clara Ward singers. I was just like a kid at Christmas. These older artists told me these great stories about being on the road with Sam Cooke and Mahalia Jackson, and it was like a grandfather telling the grandkid about the good old days. I would just sop it up.

Then they started dying. Marion died, and some others died, and I felt these stories have to be told. But I wasn't thinking about how to tell them.

What made you think these important stories should be compiled as an encyclopedia?

Carpenter: One day, I was feeling sort of frustrated as a publicist. One of my clients had made me angry (chuckling). When I get really angry, I clean up. So, I was cleaning up my closet and discovered some profiles I'd written for a book I'd planned to do on black entertainers. I thought, This is what I can do. I can do a gospel encyclopedia.

At first, I figured it would take me about four weeks to write 100 profiles. But as I interviewed people, they told me stories about the people who influenced them—people I'd never heard of. So, my whole month theory turned into over a year. The 100 artists became more than 600.

What are some of the interesting stories you discovered?

Carpenter: I've written about Willa Dorsey, who was one of the first black women to integrate white churches in the '50s and '60s as a singer. She spoke about how that felt and how she was treated. She was a trailblazer, and she's almost been forgotten. I also write about Sara Jordan Powell, who claims that Ray Charles stole her version of "America the Beautiful."

You tell of the story of Sister Rosetta Tharpe, who was torn between her desire to do mainstream music and her desire to be part of the gospel community. It seems like that is one of the stories for the ages, emblematic of the tensions many artists face.

Carpenter: Yeah. I think it will always be, because it goes back to the Scripture that says to be in the world but not of the world. How long can you be around something and not be a part of it? Rosetta Tharpe became a star doing gospel music that crossed over, but because it crossed over, offers came to do secular music, which she did. At the same time, in her heart she was still a gospel singer, and she still felt a need to minister. But the church of the time felt that you couldn't be at the club on Saturday night and come to church on Sunday morning. So once she was doing secular music, she had to stay out there, because no one would accept her back.

Because we don't live in a vacuum, or in a religiously homogenous society, those issues still exist. For example, when Yolanda Adams sang the song "Imagine" at a John Lennon tribute, some church folks felt she shouldn't have been on the show. Others didn't mind her doing the show, but felt she should have sung gospel. Still others were all for it, were happy to see her there. So you have all these different thought processes, and I don't know who's right and who's wrong. It's real tricky, and I don't think it's getting any easier, because most of the younger gospel artists want to sing gospel, but they want to be in the secular spotlight.

Because we don't live in a vacuum, or in a religiously homogenous society, those issues still exist. For example, when Yolanda Adams sang the song "Imagine" at a John Lennon tribute, some church folks felt she shouldn't have been on the show. Others didn't mind her doing the show, but felt she should have sung gospel. Still others were all for it, were happy to see her there. So you have all these different thought processes, and I don't know who's right and who's wrong. It's real tricky, and I don't think it's getting any easier, because most of the younger gospel artists want to sing gospel, but they want to be in the secular spotlight.You also talk about several artists who find themselves on music's color line, between CCM and black gospel music.

Carpenter: That's true. And I've also noticed that while we often hear about problems that black artists have in the white Christian world, we rarely hear how racist the black Christian world is. I'm friends with Martha Munizzi [who is white] and her husband, Dan. When she won the Stellar Award for best new artist in 2005, a lot of people were very upset. People said, "Who is she, where did she come from, and why is she winning our award?" I noticed the same thing when I did PR for Vicki Yohe and her album Because of Who You Are. We went to a TV station to record a black TV show, for her to sing the song. They did not know she was white. Everybody was friendly with me, but sort of cold toward her. She told me that happens a lot. They thought she was going to sing some sort of CCM music. But after she sang, the same people who acted like they didn't want her to touch them when she walked by, they rushed to her and said, "I had no idea that was you [on the radio]—you're so wonderful!"

It's common to hear that white Christian radio will not accept black artists. Yet we have a Larnelle Harris, we had a BeBe and CeCe Winans, we have a Nicole C. Mullen—all on "white radio." Now we have Vicki Yohe and Martha Munizzi. But I've had radio announcers tell me that they wouldn't play them, also.

The book includes more than one story of people who had to hold on to their faith when they were mistreated by people in the gospel music industry.

Carpenter: One of those very compelling stories is that of Rev. Willie Morganfield. He wrote this gospel classic, "What Is This," that Brother Joe May claimed to have written. Because of Brother Joe May's actions, and because the song was such a well-written, classic-sounding song, people thought it was a hymn. So all kinds of artists started recording it as a public domain song. It took years for Rev. Morganfield to get his copyright back. He died unexpectedly, just three weeks after I interviewed him.

Another compelling story is that of Phillip Bailey [from Earth Wind & Fire]. After becoming a Christian and recording a gospel project, he ended up leaving the gospel music industry disillusioned. He was pressured to create gospel music that sounded like his secular pop, and he was also surprised at the racism, lack of integrity and profiteering he saw. Still, that didn't change his faith. He realized that faith isn't about those people, but about his personal relationship with God.

There seems to be a thread of truth-telling throughout the book. For example, you don't avoid talking about the personal or financial struggles of some artists in the book. How have people responded to that?

Carpenter: Well, I've gotten the most flack from people who were close to James Cleveland. [The book describes the scandal and financial disarray that emerged after Cleveland's death, including an allegation of sexual misconduct involving a teenage boy]. I was in Los Angeles at the House of Blues, and the Clara Ward singers were there. One of the members took me outside behind the building and argued with me about the James Cleveland entry. She didn't say that any of the information was false—she just didn't like that I'd written about his wealth or the scandals. But I'd tried to speak to people who were close to him, and they refused to talk to me. Another author circulated a petition to have the book removed from stores in Chicago because he was disgusted by that entry.

Why did you feel it was important to tell those stories that point out the personal failures of gospel artists—or the failures of the industry?

Carpenter: I think that many people are turned off by the hypocrisy they see in the church. As long as we put our psalmists, musicians, and pastors on a pedestal and we cover it when they mess up, we create an unrealistic situation for people to aspire to. But when you let people know that even great people struggle, but they overcome and triumph, it gives them hope. We're striving toward perfection, toward the more Christlike life. And that takes time, and you get off the road sometimes, and hopefully you get back on the road. That's why I felt it was important for people to know.

Still, the book doesn't have a scandalous tone. And there are plenty of stories of triumph, even in difficult circumstances.

Carpenter: Right. Most of the stories are stories of triumph. One is Kirk Franklin's story of overcoming his addiction to pornography. Another is the story of Willa Ward, the sister of Clara Ward. Their mother, Gertrude, was a stage mother in the worst sense of the word. She kicked Willa out of the group, because she felt that Clara was the star. But Willa has forgiven her mother, and now allows Madelyn Thompson, one of the Clara Ward Singers, to preserve the family heritage. The way she put her feelings aside to forgive is a triumph.

Then there are stories like Douglas Miller's. One of the darkest days of his life was also the day when he wrote the famous song, "My Soul Has Been Anchored in the Lord." There were guys standing outside of his hotel room with guns, ready to kill him, because of a dispute with his record label.

With his Christian record label?

Carpenter: Yes. Out of that terrible period was born this song that has touched people's lives. People have shared with him that the song has kept them from committing suicide.

The overarching story is how, in spite of the ups and downs these artists experienced, they maintained their faith, or it was strengthened by what they went through. That's where the title comes from. "Uncloudy Days" is a song talking about getting through this world of many storms, to that place where there are no more clouds.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)